A warning to readers: As far as physics goes, I tend to use this blog to muse out loud about things I am trying to understand better, rather than to provide lapidary intuitive summaries for the enlightenment of a general audience on matters I am already expert on. Musing out loud is what's going on in this post, for sure. I will try, I'm sure not always successfully, not to mislead, but I'll be unembarassed about admitting what I don't know.

I recently did a first reading (so, skipped and skimmed some, and did not follow all calculations/reasoning) of Robert Wald's book "Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime and Black Hole Thermodynamics". I like Wald's style --- not too lengthy, focused on getting the important concepts and points across and not getting bogged down in calculational details, but also aiming for mathematical rigor in the formulation of the important concepts and results.

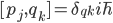

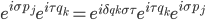

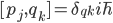

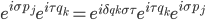

Wald uses the algebraic approach to quantum field theory (AQFT), and his approach to AQFT involves looking at the space of solutions to the classical equations of motion as a symplectic manifold, and then quantizing from that point of view, in a somewhat Dirac-like manner (the idea is that Poisson brackets, which are natural mathematical objects on a symplectic manifold, should go to commutators  between generalized positions and momenta, but what is actually used is the Weyl form

between generalized positions and momenta, but what is actually used is the Weyl form  of the commutation relations), doing the Minkowski-space (special relativistic, flat space) version before embarking on the curved-space, (semiclassical general relativistic) one. He argues that this manner of formulating quantum field theory has great advantages in curved space, where the dependence of the notion of "particle" on the reference frame can make quantization in terms of an expansion in Fourier modes of the field ("particles") problematic. AQFT gets somewhat short shrift among mainstream quantum field theorists, I sense, in part because (at least when I was learning about it---things may have changed slightly, but I think not that much) no-one has given a rigorous mathematical example of an algebraic quantum field theory of interacting (as opposed to freely propagating) fields in a spacetime with three space dimensions. (And perhaps the number of AQFT's that have been constructed even in fewer space dimensions is not very large?). There is also the matter pointed out by Rafael Sorkin, that when AQFT's are formulated, as is often done, in terms of a "net" of local algebras of observables (each algebra associated with an open spacetime region, with compatibility conditions defining what it means to have a "net" of algebras on a spacetime, e.g. the subalgebra corresponding to a subset of region R is a subalgebra of the algebra for region R; if two subsets of a region R are spacelike separated then their corresponding subalgebras commute), the implicit assumption that every Hermitian operator in the algebra associated with a region can be measured "locally" in that region actually creates difficulties with causal locality---since regions are extended in spacetime, coupling together measurements made in different regions through perfectly timelike classical feedforward of the results of one measurement to the setting of another, can create spacelike causality (and probably even signaling). See Rafael's paper "Impossible measurements on quantum fields". (I wonder if that is related to the difficulties in formulating a consistent interacting theory in higher spacetime dimension.)

of the commutation relations), doing the Minkowski-space (special relativistic, flat space) version before embarking on the curved-space, (semiclassical general relativistic) one. He argues that this manner of formulating quantum field theory has great advantages in curved space, where the dependence of the notion of "particle" on the reference frame can make quantization in terms of an expansion in Fourier modes of the field ("particles") problematic. AQFT gets somewhat short shrift among mainstream quantum field theorists, I sense, in part because (at least when I was learning about it---things may have changed slightly, but I think not that much) no-one has given a rigorous mathematical example of an algebraic quantum field theory of interacting (as opposed to freely propagating) fields in a spacetime with three space dimensions. (And perhaps the number of AQFT's that have been constructed even in fewer space dimensions is not very large?). There is also the matter pointed out by Rafael Sorkin, that when AQFT's are formulated, as is often done, in terms of a "net" of local algebras of observables (each algebra associated with an open spacetime region, with compatibility conditions defining what it means to have a "net" of algebras on a spacetime, e.g. the subalgebra corresponding to a subset of region R is a subalgebra of the algebra for region R; if two subsets of a region R are spacelike separated then their corresponding subalgebras commute), the implicit assumption that every Hermitian operator in the algebra associated with a region can be measured "locally" in that region actually creates difficulties with causal locality---since regions are extended in spacetime, coupling together measurements made in different regions through perfectly timelike classical feedforward of the results of one measurement to the setting of another, can create spacelike causality (and probably even signaling). See Rafael's paper "Impossible measurements on quantum fields". (I wonder if that is related to the difficulties in formulating a consistent interacting theory in higher spacetime dimension.)

That's probably tangential to our concerns here, though, because it appears we can understand the basics of the Hawking effect, of radiation by black holes, leading to black-hole evaporation and the consequent worry about "nonunitarity" or "information loss" in black holes, without needing a quantized interacting field theory. We treat spacetime, and the matter that is collapsing to form the black hole, in classical general relativistic terms, and the Hawking radiation arises in the free field theory of photons in this background.

I liked Wald's discussion of black hole information loss in the book. His attitude is that he is not bothered by it, because the spacelike hypersurface on which the state is mixed after the black hole evaporates (even when the states on similar spacelike hypersurfaces before black hole formation are pure) is not a Cauchy surface for the spacetime. There are non-spacelike, inextensible curves that don't intersect that hypersurface. The pre-black-hole spacelike hypersurfaces on which the state is pure are, by contrast, Cauchy surfaces---but some of the trajectories crossing such an initial surface go into the black hole and hit the singularity, "destroying" information. So we should not expect purity of the state on the post-evaporation spacelike hypersurfaces any more than we should expect, say, a pure state on a hyperboloid of revolution contained in a forward light-cone in Minkowski space --- there are trajectories that never intersect that hyperboloid.

Wald's talk at last year's firewall conference is an excellent presentation of these ideas; most of it makes the same points made in the book, but with a few nice extra observations. There are additional sections, for instance on why he thinks black holes do form (i.e. rejects the idea that a "frozen star" could be the whole story), and dealing with anti de sitter / conformal field theory models of black hole evaporation. In the latter he stresses the idea that early and late times in the boundary CFT do not correspond in any clear way to early and late times in the bulk field theory (at least that is how I recall it).

I am not satisfied with a mere statement that the information "is destroyed at the singularity", however. The singularity is a feature of the classical general relativistic mathematical description, and near it the curvature becomes so great that we expect quantum aspects of spacetime to become relevant. We don't know what happens to the degrees of freedom inside the horizon with which variables outside the horizon are entangled (giving rise to a mixed state outside the horizon), once they get into this region. One thing that a priori seems possible is that the spacetime geometry, or maybe some pre-spacetime quantum (or post-quantum) variables that underly the emergence of spacetime in our universe (i.e. our portion of the universe, or multiverse if you like) may go into a superposition (the components of which have different values of these inside-the-horizon degrees of freedom that are still correlated (entangled) with the post-evaporation variables). Perhaps this is a superposition including pieces of spacetime disconnected from ours, perhaps of weirder things still involving pre-spacetime degrees of freedom. It could also be, as speculated by those who also speculate that the state on the post-evaporation hypersurface in our (portion of the) universe is pure, that these quantum fluctuations in spacetime somehow mediate the transfer of the information back out of the black hole in the evaporation process, despite worries that this process violates constraints of spacetime causality. I'm not that clear on the various mechanisms proposed for this, but would look again at the work of Susskind, and Susskind and Maldacena ("ER=EPR") to try to recall some of the proposals. (My rough idea of the "ER=EPR" proposals is that they want to view entangled "EPR" ("Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen") pairs of particles, or at least the Hawking radiation quanta and their entangled partners that went into the black hole, as also associated with miniature "wormholes" ("Einstein-Rosen", or ER, bridges) in spacetime connecting the inside to the outside of the black hole; somehow this is supposed to help out with the issue of nonlocality, in a way that I might understand better if I understood why nonlocality threatens to begin with.)

The main thing I've taken from Wald's talk is a feeling of not being worried by the possible lack of unitarity in the transformation from a spacelike pre-black-hole hypersurface in our (portion of the) universe to a post-black-hole-evaporation one in our (portion of the) universe. Quantum gravity effects at the singularity either transfer the information into inaccessible regions of spacetime ("other universes"), leaving (if things started in a pure state on the pre-black-hole surface) a mixed state on the post-evaporation surface in our portion of the universe, but still one that is pure in some sense overall, or they funnel it back out into our portion of the universe as the black hole evaporates. It is a challenge, and one that should help stimulate the development of quantum gravity theories, to figure out which, and exactly what is going on, but I don't feel any strong a priori compulsion toward one or the other of a unitary or a nonunitary evolution on from pre-black-hole to post-evaporation spacelike hypersurfaces in our portion of the universe.