On Wednesday, March 7, 2018, at the Leo Rich theater in the Tucson Convention Center, I heard two of the best chamber music performances I've ever heard. As part of the 25th Tucson Winter Chamber Music Festival, clarinetist Romie de Guise-Langlois and the Morgenstern Trio performed Olivier Messiaen's Quatuor pour la fin du temps (Quartet for the end of time), for a standard piano trio (piano, violin, cello) plus clarinet, and the Dover Quartet performed Mendelssohn's String Quartet in F minor, Opus 80. You may find in my reviews that I tend to emphasize the positive, and not belabor it when a performance could have been better, instead concentrating on how much I have gotten out of the performance that was actually given. So let me emphasize that that is not the case here: one could imagine performing these works a little differently, perhaps, but not better than was done here. This was an extraordinary, unforgettable evening of music.

The Messiaen is a piece I have valued for decades; I know it to the point of recognizing many of the themes when played in concert, but (unlike some other works) I have not internalized it to the extent of being able to replay significant parts of it in my head. I have long considered it one of the most significant pieces of twentieth century chamber music; the performance by de Guise-Langlois and the Morgenstern made it clear that it is one of the pinnacles of music of any time or place. It is inspired by the biblical book of Revelations, and deeply informed, as was all of Messiaen's music, by the composer's intense and very personal form of Catholic faith, and while it should be experienced in this light, with the aid of Messiaen's own program notes (and the obvious signposts provided by the movement titles), it is of universal value and appeal regardless of the auditor's faith or lack of faith. A translation of Messiaen's notes is included in the Wikipedia article on the piece. (References like "blue and orange chords" evince Messiaen's synaesthesia, in which harmonies evoked experiences of color.) I won't try much to describe the significance of the music or the experience of listening to it, since Messiaen's notes give a pretty good idea of what's in store. In this regard I'll just say that he is strikingly successful at achieving---roughly speaking, as the color experiences will not be available to most of us and the specific religious references are more inspiration or metaphor than something reproducible or verifiable---what he describes in the notes: the music is powerful, beautiful, glorious.

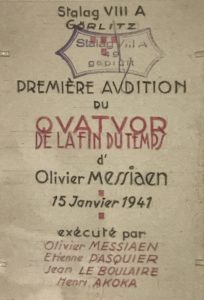

Alex Ross' 2004 New Yorker article (reviewing a book on the piece by Rebecca Rischin, and a performance by the Met Chamber ensemble) provides further valuable background and reaction to the piece, which he calls "the most ethereally beautiful music of the twentieth century". It was composed primarily in 1940-41 while Messiaen was imprisoned in the German prisoner of war camp Stalag VIII, and first performed there in 1941. Parts of it were apparently begun earlier (notably the third movement, Abîme des Oiseaux (Abyss of the Birds, for solo clarinet). I am not sure how deeply the music was influenced by the conditions under which it was composed, since in style, content, and intensity it does not seem to me radically different from his work before and after the war. It's possible that the composition of the work for a medium-size chamber group may be one of the most important effects of the quartet's origin in a POW camp---it may be my own ignorance, but most of the other great works I am aware of by Messiaen are either for piano (or piano and voice), or large groups like orchestra or orchestra with chorus.

Ross differs from Messiaen in how he describes the "Seven Trumpets" movement, writing: "the gentlest apocalypse imaginable. The “seven trumpets” and other signs of doom aren’t roaring sound-masses...". Whereas for Messiaen it is "Music of stone, formidable granite sound; irresistible movement of steel, huge blocks of purple rage, icy drunkenness. [...]terrible fortissimo[...]". How one experiences it may depend on the performance, I guess, as well as the auditor. Ross calls the "Trumpets" section "Second Coming jam sessions", and in connection with the piece overall (not necessarily this movement), my wife also mentioned a kinship with jazz. This should be understood in light of the rather wide range of jazz my wife and I listen to --- not just bebop and swing masters like Bob Rockwell and colleagues, but avant-garde artists like Charles Gayle and Peter Broetzmann, and modern if not quite avant-garde groups like Kenny Werner's quartet, Charles Lloyd with Bill Frisell, and the Billy Hart Quartet, just to mention a few groups we have recently heard live. Indeed, the Lloyd/Frisell combo and the Hart quartet (with Ethan Iverson on piano, Mark Turner on sax, and Ben Street on bass) are especially prone to episodes of Messiaenic intensity: continually evolving ecstatic/reflective grooves, carefully crafted harmonic coloration, dancing rhythmic complexities, calm serenities bringing to mind Baudelairean realms where "tout n'est qu'ordre et beauté, / Luxe, calme et volupté".

As I said above, the performance by de Guise-Langlois and the Morgenstern was one of the best things I've ever heard. Clichés like "riveting", "stunning", etc...apply without reservation and quite literally: my attention did not wander for a moment during the long performance, and the audience sat in the proverbial stunned silence for ten or twenty seconds after the musicians lowered their bows and instruments, before breaking into a standing ovation. Of course, S.O.'s have become disconcertingly common these days (it especially annoys me when people stand and clap as a prelude to an early run for the exits), but this one was fully deserved. Ross' generally positive review of the performance he attended remarks that it "lacked the total unanimity that makes a great performance of the Quartet seem like a mind-reading séance". This performance had no such lack, although our close vantage point in this relatively small auditorium disclosed that the mind-reading was taking place in the usual way, through ears and eyes, as they very actively looked at each other, nodded for cues, sometimes swaying to the music. It was indeed a kind of séance. De Guise-Langlois' clarinet playing is remarkable in its dynamic and expressive range and sensitivity to the other musicians; I got the impression (perhaps misguided) that her attention to the other musicians may have been the crucial ingredient binding them into a unit capable of such a sublime achievement. She has a wide range of expressive timbre at her command, but overall I would say skewed toward clarity and purity of tone. Catherine Klipfel's tone, on a Steinway D, was great for this piece, bell-like with just enough of a touch of hollowness and edge to add complexity and not to be icily pure. Everyone played superbly and I will be on the lookout for the Morgenstern and de Guise-Langlois in other repertoire. De Guise-Langlois seems to me clearly a rising superstar of the classical clarinet. I didn't find any single link at Youtube that I felt gives an adequate idea of the full range of what she can do, in a sympathetic medium-size chamber context. I did very much like a contemporary (though relatively conservative stylistically) duet with piano, composed by Kevin Puts.

The space above the stage in the Leo Rich auditorium was larded with microphones for this performance, and highlights of Tucson Chamber Music Festival are eventually broadcast on Classical KUAT-FM, 90.5/89.7 FM, so I recommend trying to find out when this will happen and streaming the broadcast over the web. (It may be a long time from now, though.) I would be thrilled if it eventuated in a full-fidelity digital recording---the Arizona Chamber Music Association does sell CDs of past festival highlights, so we can hope this performance will appear on such a disc in the future.

Ross recommends the 1975 recording by Tashi as "still unsurpassed" (at least in 2004). I have long had this on LP, but have done most of my listening to this Deutsche Grammophon CD featuring Daniel Barenboim on piano (Youtube link here). I also recall getting a lot out of an excellent performance at the Santa Fe Chamber Music festival in the 1990s, and a really wonderful performance of the solo clarinet movement at the Smithsonian American Art Museum's concert series a few years back. I think it was part of a concert by the ensemble Eighth Blackbird. I haven't revisited the recordings I own since the Tucson concert, because I don't want anything to displace it in my memory, although I think it is now time to start listening, as this is a piece of music I want to "git in my soul," as Charles Mingus might say.

I'm not sure if I'd heard of the Dover quartet before this performance of the Mendelssohn. I quickly decided that the Dover is one of my favorite string quartets ever. String quartets can sometimes sound strident---an effect that may depend partly on the type of strings they are using. The Dover was anything but, with a warm, even at times mellow timbre that nevertheless had plenty of texture and was compatible with great intensity and drive where needed. The F minor quartet, Opus 80, was composed in the shadow of the death of Mendelssohn's beloved sister Fanny; within a few months of its composition, Mendelssohn too was dead. It is a masterpiece, and the Dover did it full justice. The outer movements had plenty of intensity. The slow movement had a bit more autumnal, meditative, mellow pastoral feel --- I had a sense that this movement, too, could have been given more intensity and a different, more anguished, emotional tone in places, but not the sense that such an interpretation would have been preferable, particularly in light of the Sturm und Drang that was often in evidence in the outer movements. An outstanding performance, also fully deserving of the standing ovation that ensued.